Naturally Nuclear

Gaining Hope Before Losing Dad

by Heather Hoff

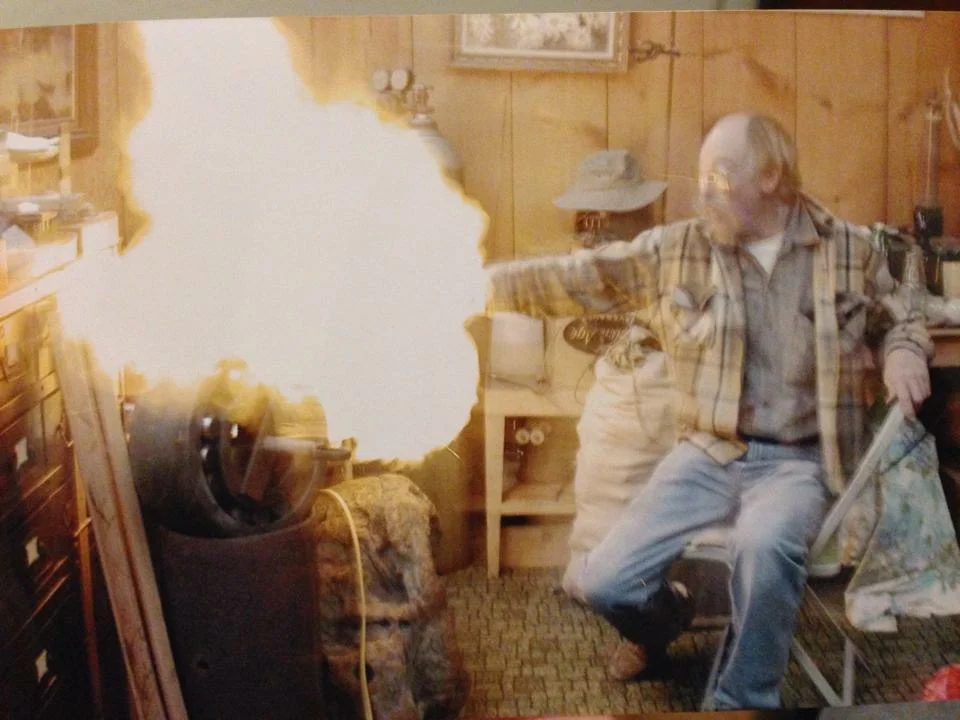

When I was nine years old, my dad burnt all the hair off his face. The explosion might have been from hydrogen gas, but I'm not sure - there was no shortage of combustible materials in the workshop he called “Irons in the Fire.”

Irons in the Fire sat between the state highway and our trailer, which was parked in a place called “Top of the World. We were seven miles from the city of Miami — Arizona — and had no neighbors for a half a mile around us. We had a composting toilet, massive oak trees, and any given day, a random collection of machine parts and electronics strewn around the property.

Dad looked every bit the mad scientist. Irons in the Fire became a field trip destination for my school. Dad would use a blacklight to make uranium fluoresce and shoot sparks from the top of his Tesla coil. He earned money doing woodworking, welding, chainsaw maintenance, and landscaping. His largest passion was glassblowing.

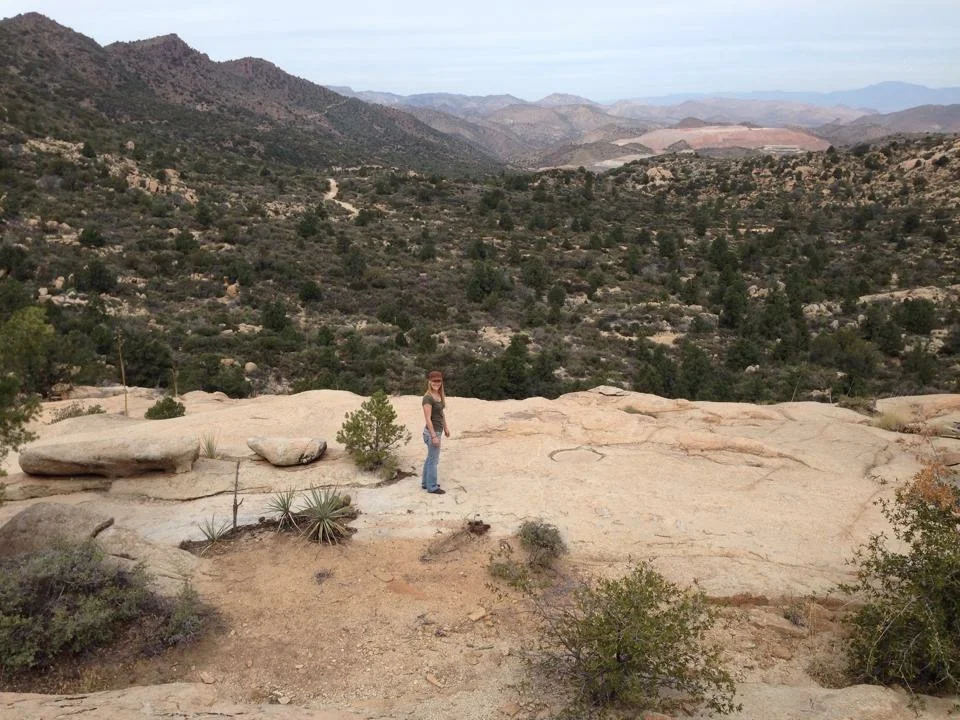

My sister and I spent most of our days between state highway 60 and neighboring Forest Service land, climbing through caves and over boulders, and avoiding rattlesnakes and javelina. We found ancient pottery and arrowheads, and I dreamt of being an archaeologist. Sometimes I still dream I am navigating the paths from our trailer to the best spot on the rocks for watching stars.

We never had enough water. When we were little, showers consisted of Dad sprinkling us with a watering can outdoors. He built an elaborate system of hand-welded steel tanks to store a reserve of water, but the well was still a poor producer. We often drove to town to fill up water tanks. I never experienced any of it as a hardship, but I knew our lives were different.

I later became extremely bothered by other people’s waste. One of my earliest memories was being near tears when, after gymnastics class, a girl turned the water faucet on full blast to wash her hands. “Turn it down!” I pleaded to her. “Why?” she asked. “It’s not my water.” I felt slapped.

Mostly I loved nature by being in it. In high school I was president of the environmental club, which consisted of exploring Arizona with friends. Over my bed hung a poster of animals sitting atop planet Earth. The headline read: “They were here first.”

In college in Tucson, my concerns about waste returned. I became co-leader of the campus recycling program. I spent hours sorting through people’s trash for things that could be recycled, the whole time growing more upset that nothing seemed to persuade people to sort their bottles and cans. It was nasty work, and I hated doing it. But I felt I had to.

Dad also had strong views about the environment. He was always reading newsletters from groups like the Union of Concerned Scientists. He was pessimistic about humankind. When I first started thinking about having children, he told me “You’re making the wrong choice. We’re destroying the planet and it will be a hard life for your kids.”

After college I made rectal thermometers for cows, worked a harvest season at a winery, and sold retail clothing. Finally I decided I should start a more serious career, so I applied for work at Diablo Canyon.

Before I went to work there, my uncle, a physics professor, told me he had heard stories of workers getting “hot” particles in their lungs, and dying from cancer. Some other relatives said it's not a good place for a young female to be working.

I was born three months after the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant meltdown. (My mom says she and Dad were “silently protesting” it as “Top of the World” offered no louder alternatives.) I had heard all the things people said, so I turned my efforts to trying to understanding every aspect of the plant, and answering all the questions in my mind. How much radiation is safe? What happens to the waste? What happens in an earthquake?

My curiosity turned to excitement. I was surprised at how good I felt learning systematic thinking, practicing observation and questioning, and troubleshooting. I learned basics about the plant, and eventually became a reactor operator.

My dad, like me, became increasingly curious and optimistic about my career. One time, when I came to visit, he asked me to describe how Diablo Canyon generates power. I drew it for him. The permanent magnet on the end of the shaft spins and creates a magnetic field. The field creates alternating current in the rotor. The exciter converts it into direct current. The DC in the rotor creates an alternating current in the stator, and from there, it goes out through our transformers and onto the grid.

He leaned back in his chair and was quiet for a moment. “That’s so amazing.” He said he never would have imagined that such a large system would be self-excited — that it could go from nothing to enough power for three million people. He asked me walk him through it all again.

Despite what Dad said about why I shouldn’t have kids, after I went into labor he and my mom jumped in the car to drive 10 hours and meet our new daughter. He was the happiest I’d seen him in a long time.

Dad was always a bit eccentric, and it took us all a while to realize that his behavior was changing. The problem was even more apparent when he dropped my daughter, who was five months old at the time. He had a rare dementia that shrank his frontal temporal lobes, at first affecting his personality and language, then later, his memory. Four years later he was dead at the age of 71.

I often found myself wondering about all the chemical exposure he got from glass blowing, metal-working, and his other hobbies that seemed to invariably require large quantities of toxic chemicals. I won’t ever know, but chemicals make me much more nervous than radiation because of how they accumulate in our bodies and mess with hormones and metabolism and all kinds of biological processes.

When he was really sick, I sat with him and told him about my job. He had become proud that I worked in a career that generated such a large quantity of greenhouse gas-free electricity, while simultaneously being a great fit for my skills and personality. Whatever anti-nuclear sentiments he once had were now ancient history; something close to the opposite had settled in. My descriptions of the power plant gave him comfort. When he got to the point where he could barely hold a conversation, he once broke the silence and asked, “Can you tell me again about the main generator?

Over the years I’ve grown to love Diablo Canyon and to see nuclear power as essential to solving climate change and leaving a better world for future generations.

In the 12 years I have worked at Diablo Canyon this is the first time I've spoken out publicly about nuclear. When I first realized that there are numerous barriers that could cause the plant to cease operations, even before attempting license renewal in 2024, I felt compelled to speak out. Kristin and I will both be fine and are not worried about finding work somewhere else if they close Diablo. But we feel upset at misinformation and emotional targeting that is driving people to want to close it. And, we do love our jobs.

In addition to being a hub for innovation (we are continuously upgrading systems), Diablo Canyon is a showcase of our natural environment. We often watch humpback whales leap out of the water from our office windows. Pelicans and sea lions lounge atop the rock walls of our intake structure not far from the parking lot — where you can charge your electric car. My neighbor says that his best California scuba experience was just off our coast.

Diablo is also one of the most controversial nuclear plants in the world. In 1981, 2,000 people were arrested protesting its construction. The singer David Crosby recently showed up to testify against the plant in his Tesla, which he may not realize is partially charged with nuclear energy.

“We might be destroying the planet, just like my dad thought. But in the end, we both came to think that humanity is smart enough to save it.”

If Diablo Canyon is closed, it will be immediately replaced by natural gas, not solar and wind. There is a connection between all the natural gas California burns and solar and wind. Solar and wind are intermittent, and don't necessarily match up with grid demand. Gas helps even out the supply.

Our plant has typically been a base-load plant, meaning we virtually always operate at 100% power. Now we are considering how to implement "flexible operation" so that we can help accommodate the growing renewables market. Apparently gas plants suffer a lot of efficiency losses and are even more polluting when forced to ramp down below certain levels. Relying more on gas plants, and less on our one remaining nuclear plant, means we have to store more gas. There was recently a massive natural gas leak in southern California at Porter Ranch/Aliso Canyon. Not only did this completely blow through California's GHG emission goals for the year, but now there is not enough gas in reserve, and some groups are predicting rolling blackouts. During blackouts, people die.

Beyond environmental concerns, I worry about a society that would give up advanced technologies like nuclear out of fear. In one of my dad's favorite books, the author talks about how at different times, societies have given up on technologies for various reasons, and how later that decision backfires on them.

Over the last few weeks, I've decided to start speaking out even more, and offer a chance for dialogue. I am interested in talking with anyone who wants to know more or has questions about nuclear. I would love to talk with Sierra Club and other environmental groups to help communicate that we want the same things. I want to share my experience and also understand their concerns.

We are allowed by our employer, PG&E, to communicate on social media and blogs, like this one. We did not ask their permission to do this and they did not ask us to do promotion. Nothing in this forum should be interpreted as representing PG&E.

I believe we care about and want the same things as most Sierra Club moms and members. We want everyone in the world to be able to care for their children like we can for ours. We want a world of less air pollution for our kids. I changed my mind about nuclear, and my dad changed his mind, too. We might be destroying the planet, just like my dad thought. But in the end, we both came to think humanity is smart enough to save it.

Heather Hoff is mother to Zoe and a former reactor operator and procedure writer at Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant in San Luis Obispo, CA. She is a co-founder of Mothers for Nuclear. This article represents her opinion alone.

-April 24, 2016

Me at "Top of the World," Miami, Arizona

Dad in "Irons in the Fire"

My sister, out on the rocks near "Top of the World," Arizona

The underside to "Top of the World"

Canoeing with Dad

Diablo Canyon, California's last nuclear plant

Me, in the Control Room

We can have pristine nature & no pollution around Diablo Canyon or...

...more catastrophic natural gas leaks!

Kristin and me after a long day urging members of Congress to save Diablo Canyon.