Katherine Ward

I am not a scientist. I am not an engineer. In fact, for most of my grade school and secondary school education, I actively ran as far away from math and science as possible. I was the stereotype. The girl who loved to write, to sing, to dream. So much so that I chose a university degree and a career that let me use my love of writing to help others tell their stories—to employees, to markets, to publics. But somewhere along the way, the aversion to science must have rubbed off, and I have spent my 30+ year career in communications working alongside scientists and engineers.

I fell into the nuclear industry a bit late—in 2006—when a “life event” forced me back to full-time work to support my kids. It didn’t matter who was the employer. I could tell stories, and a job was a job, so I grabbed it. Only then did I start to realize what I had joined up to, and how incredibly smart my colleagues were.

I wasn’t really scared of nuclear—I didn’t even know enough about it to be scared. And I certainly had no idea that my province of Ontario is powered by so much nuclear energy. On any given day, it’s about 60%. When it dawned on me that every second video game my kids played, every second meal I cooked, every second time we flipped on the light switch, it was enabled because of nuclear— this industry I’d become part of—that’s when the learning really began.

Because my employer was, in fact, the designer and builder of Canadian CANDU technology, there was a lot to learn, not just about how the reactor works and its place in the market, but also about its ability to produce medical isotopes for cancer detection and for medical instrument sterilization among other things.

I was incredibly proud when Ontario shut down its last coal-fired power plant, due largely to two CANDU reactors—something I was tangentially involved with—being refurbished and brought back into service in 2012 in Ontario. The life extensions for plants continue, and the industry is working to ensure on-time, on-budget refurbishments so our businesses and our citizens can have 30 more years of affordable low-carbon energy.

When I realized that this was significantly decreasing the number of smog days in southern Ontario, another lightbulb went on. Nuclear was helping kids with asthma and seniors with breathing issues. We were literally making it easier to be outside—and to be active.

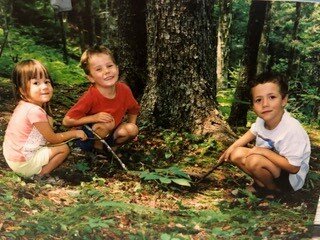

That’s important to me. I grew up in a small town, and although I have Iived in a big city most of my adult life, I have done my best to make sure that my three (now grown!) children have a healthy appreciation and love for nature. Together and separately, we have hiked, biked, canoed, and kayaked much of the province. All three have worked at summer camps where they’ve passed that same love on to other children. In fact, my middle child has spent the past three summers planting trees, taking another step towards clean air. While he does that, I putter around in my little suburban garden, growing as many native plants as I can for our bees, bugs, and butterflies. Next year, I hope to get some milkweed established just beyond my fence in the hopes of seeing more monarchs.

Nuclear continues to be a learning journey for me, as I delve more into spent fuel management and the challenges there. I have full confidence that the bright minds around me are solving these problems. My job is to help them tell that story and encourage the public to not only keep an open mind to nuclear, but realize the value it not only can bring, but that it is bringing right now.