Fukushima: Perspective from a Reactor Operator

It was with a skeptical attitude that I first started my job at Diablo Canyon. I’m generally trusting of people until they prove themselves unworthy; but with technology, it’s the other way around - I’m initially skeptical and trust must be earned.

My skepticism manifested itself in relentless questions, as I am generally curious and love to learn from people and conversations. First, I tried to understand everything about how the plant works, what’s the deal with the waste, and what happens in abnormal situations. My colleagues in initial operator training were often annoyed with my questions in class – “but what about this?” and “how does that work?” – especially on Friday afternoon at 4:30pm. After I understood plant operations, I moved on to questions about every possible thing that could go wrong, and the consequences.

I won’t say all those questions were easy to answer – it took me many years. But I was eventually satisfied that by helping the plant to run efficiently, I was in agreement with both my environmental and humanitarian values. Not only does nuclear have relatively small impacts on nature, it also provides an enormous amount of emission-free electricity.

Me in the Diablo Canyon Power Plant Turbine Building (Arellano, 2004)

My questioning attitude hasn’t stopped - I am constantly reevaluating the benefits and risks of nuclear. When I uncover information that challenges my position on nuclear energy, I start the questioning process all over again - equally ready to change my mind or to reaffirm my support.

When life-altering experiences occur, we tend to remember exactly where we were, and what we were doing. In a very similar way to 9/11 (I was about to get on a plane to fly to New York), I remember the events now referred to as 3/11. On March 11, 2011, I was called early in the morning to come into work. I was told that Avila Beach, which was on the route to Diablo Canyon, would soon have restricted access.

At the Reactor Operator controls, Diablo Canyon Unit 1

Upon arriving in the Control Room at Diablo Canyon, I learned that there had been a large earthquake in Japan (1), and there was a tsunami watch for our area of California. As Operators in the Control Room, my coworkers and I took extra precautions. We reviewed our abnormal operating procedures to ensure we were familiar with any range of scenarios. We stood at attention through the multiple hours when it was predicted that tsunami waves would arrive on the Pacific coast. We watched for abnormal conditions that would affect our ability to provide cooling water from the ocean to the plant. We knew if there was a significant drawdown, we would need to take some temporary actions until the ocean returned to normal.

That day turned out to be uneventful at Diablo Canyon, but over the next few days, my convictions about nuclear energy were turned upside down. There were various stories about what was happening at some nuclear power plants in Japan. The rumors sounded bad - almost unbelievable. At first I felt dismissive of the idea that anything significant could be happening there. After all, I had spent all these years developing and affirming my support for nuclear technology. But then, I saw the video. Someone turned on the news, and I saw replay after replay of one of the reactor buildings at Fukushima Dai-ichi exploding.

Fukushima Dai-ichi during explosion of reactor building due to hydrogen buildup. (Reuters, 2011)(2)

My heart instantly filled with fear – fear of what it would be like to be a Control Room Operator there, fear of what it would be like to be wondering if coworkers had been hurt or killed, and fear that I didn’t understand why this was happening. It seemed like no one had reliable information.

Operators at Fukushima Dai-ichi in a completely dark control room.

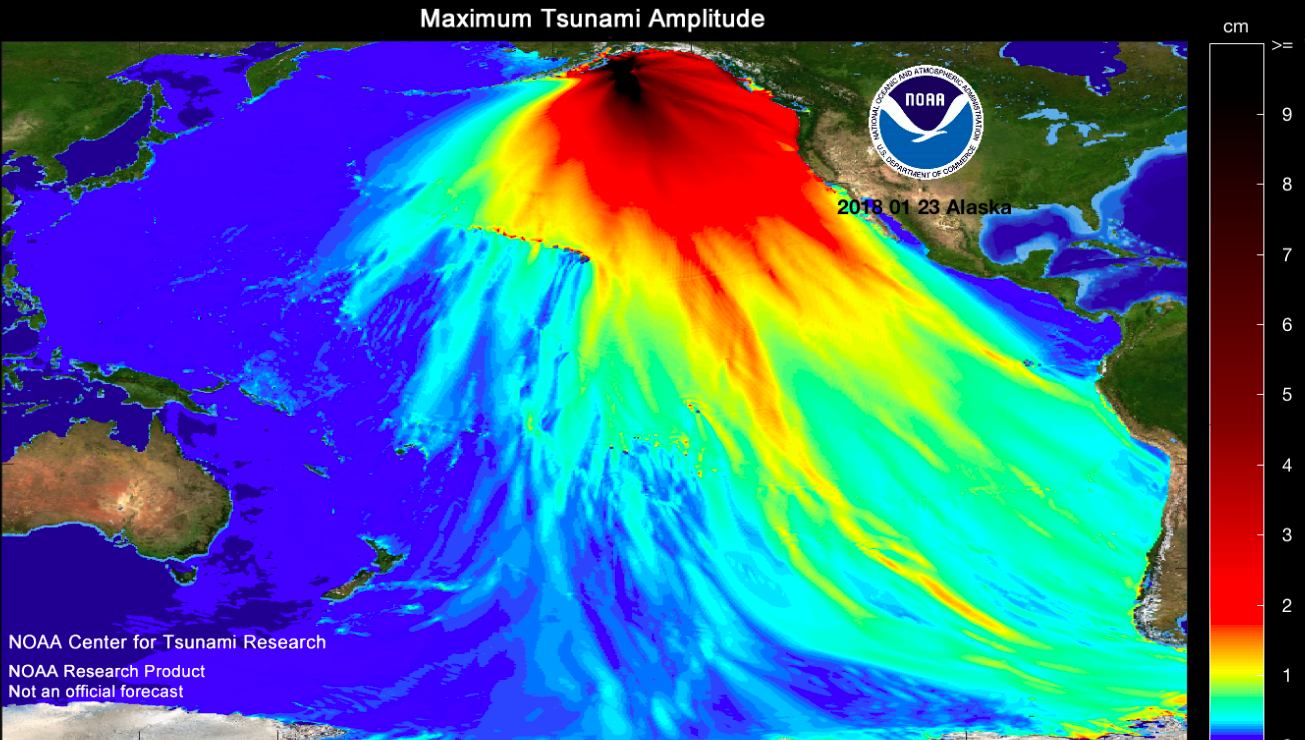

It was a while before accurate information was available, and unfortunately it did not reduce the presence or popularity of fear-inducing propaganda. Some media and advocacy groups had a heyday making up the worst-imaginable scenarios. One particular example that stands out in my mind was the graphic that anti-nuclear activists were (and still are) calling a “map of radiation” spreading outward from Fukushima. This graphic is actually a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) representation of the tsunami wave height.

Tohoku Earthquake (NOAA, 2011)(3)

Kodiak Earthquake (NOAA, 2018)(4)

A similar map from January 23, 2018.

In addition to the “radiation” map above, there is still a wide range of misinformation available on the internet. Google image searches for 'Fukushima' return lots of scary things, including pictures of burning natural gas plants and oil refineries.

Natural Gas Plant, (Fukushima Google Images Search)

Nippon Oil Refinery (US Navy, 2011)

As I learned more about the details of both short- and long-term impacts of the accident, it became clear that our fears were largely misdirected. Even in this horrific-sounding scenario, the human health impacts resulting from the accident were caused by the evacuation, and not by radiation or by any events at the plant itself.(2, 5) The situation at Fukushima Dai-ichi was stable, and international teams were joining together to develop innovative new solutions to the challenges at the site.

A lot has changed since 2011. Kristin and I started Mothers for Nuclear in April 2016 because we realized that nuclear plants were shutting down early around the country and being replaced primarily with fossil fuels. We also realized that many of the challenges faced by nuclear energy are a result of misperceptions, including those surrounding the events at Fukushima.

Art by Aileen Abd, Mother for Nuclear.

We get a lot of questions about Fukushima, and even after learning more of the technical aspects of the plant and the recovery activities, it still felt like something was missing. On Feb 4, 2018, I was able to see the site for myself and evaluate the issue from a new perspective.

Tanks at Fukushima Dai-Ichi (Japan Daily Press, 2017)

When I visited Fukushima Dai-ichi, I felt an emotional reaction similar to the one I felt seven years ago in the control room of Diablo Canyon – fear, disbelief, empathy, and sorrow. It’s hard to fathom something powerful enough to cause such damage to concrete and steel, and in this setting it’s even harder to separate emotions from facts and reason. Sometimes the hardest things to think about are also among the most important - a technology that produces large amounts of emission-free energy on a relatively tiny land footprint addresses our biggest environmental and humanitarian challenges, and it’s something that deserves open minds and honest evaluation.

As we drove through the evacuation zone, I saw empty towns - abandoned after the earthquake and tsunami and now frozen in time due to hurried evacuations. Although the levels of radioactivity in the area are low, these towns now face a difficult question - to rebuild or not to rebuild?(8) Towns require infrastructure - water, electricity, schools, grocery stores. Radioactivity is no longer the issue here; the deferred rebuilding effort and the current lack of infrastructure prevents residents from returning home.

When we reached the Fukushima Dai-ichi site, I saw contrast after contrast. New office buildings next to damaged structures. Intact reactor buildings next to the twisted metal and crushed concrete of Units 1, 3 and 4. Beautiful forests and cherry trees next to wide expanses of asphalt and concrete. Abandoned and rusting bolted steel tanks next to new welded tanks, waiting to hold water that has been cleaned of all contaminants except tritium. A calm ocean next to tsunami-damaged tanks and roads. Thinking of the forces that caused this damage is scary, and it’s not something anyone ever wants to be repeated.

While it is tempting to change my position based on emotion alone, but the truth of this situation, when I purposefully put aside my emotions, is that everything must be considered in context. Lots of industrial sites are huge. Lots of them have concrete and tanks. Accidents happen at other places, and with much greater frequency and much more impact to human health (e.g. natural gas plants and oil refineries such as those shown above). Lots of disasters kill lots of people. Also, lots of people die in ridiculous, careless ways, and for unjustified activities (e.g. the Darwin awards).

Here is just one example from my hometown of San Luis Obispo, California. There is a road called Tank Farm that travels across a wide expanse of rushes and marshland, with tall chain-link fences lining both sides of the road. Built in 1910, the Unocal tank farm was a major storage center for oil from the San Joaquin Valley. It contained six large underground storage reservoirs as well as 21 above-ground steel storage tanks. In 1926 there was a lightning strike in between the tanks that caused an explosion. Four of the tanks erupted in a blaze that spread to other tanks and across the land on rivers of oil. During the blaze and explosion, burning timbers were ejected from the site and found up to two miles away. Ash rained down throughout the whole county, and the fire was seen from as far away as Fresno, CA.(7)

Eight million barrels of oil were lost, and the whole area is contaminated and has been restricted since almost a century ago! By happenstance perhaps, the site is nearly identical in size to Fukushima Dai-ichi.(6)

These maps show the two sites in comparison, on the same scale.

Tank Farm remediation site: 332 acres (Google Maps, 2018)

Fukushima Dai-ichi site: 370 acres (Google Maps, 2018)

Industrial accidents happen A LOT and cause widespread damage and destruction. We often don't even pay attention to news stories about pipeline explosions or oil spills – they are too common. Commercial nuclear power, on the other hand, has only had three significant accidents. Everyone knows about these three - because there are only three. Providing large quantities of emission-free electricity with very little environmental impact is an activity that justifies a certain amount of risk - it is worth the cost.

We don’t have to be emotionless robots to accept nuclear energy or accept the fallout (no pun intended) from Fukushima. This was hard for a lot of people, for lots of different reasons. It’s also okay to feel bad about the consequences, and to improve our processes to be even better. If we look at the positive and negative sides of all the different energy sources, it becomes clear that there are risks and trade-offs involved in everything.

Knee-jerk reactions to major events can cause worse outcomes for everyone in the end. There is a lot to learn about the accident at Fukushima, and I have gained a wealth of technical knowledge about the event through my training as a reactor operator. However, technical solutions alone are not enough to solve the problems that remain. After visiting Japan and seeing Fukushima Dai-ichi for myself, I am better able to see the bigger picture. As Japanese citizens in Tokyo and other major metropolitan areas breathe toxic air due to fossil fuel emissions, fear of nuclear power and low public opinion hamper the country's ability to re-start what was once their largest source of clean energy.

Emotion can prevent us from solving this problem, or it can shift to help propel Japan and the rest of our world into support for a clean energy mix. This won't happen by itself, people must be willing to challenge their mental models and question their opinions. Emotion can be powerful, but knowledge combined with emotion has the power to change our world.

-Heather

References:

USGS (2016) M9.1 Near the East Coast of Honshu, Japan. Retrieved from: https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/official20110311054624120_30#executive

Reuters (2011), Japanese Government Orders Evacuation Of Fukushima Plant. Retrieved from: http://www.neontommy.com/news/2011/03/japanese-government-orders-evacuation-fukushima-plant

NOAA (2011), Tohoku (East Coast of Honshu) Tsunami, March 11, 2011, Main Event Page. Retrieved from: https://nctr.pmel.noaa.gov/honshu20110311/

NOAA (2011), Kodiak, Alaska Tsunami, January 23, 2018 Main Event Page. Retreived from: https://nctr.pmel.noaa.gov/alaska20180123/

Harding, Robyn (2018) . Fukushima nuclear disaster: did the evacuation raise the death toll? Financial Times. Retrieved from: https://www.ft.com/content/000f864e-22ba-11e8-add1-0e8958b189ea

San Luis Obispo City (2017). Chevron Tank Farm Remediation and Development Project. Retrieved from: http://www.slocity.org/government/department-directory/community-development/planning-zoning/specific-area-plans/chevron-tank-farm-area

David Middlecamp (2018). San Luis Obispo Tank Farm Fire. SLO Tribune. Retrieved from: http://sloblogs.thetribunenews.com/slovault/2010/01/san-luis-obispo-tank-farm-fire.

Fukushima Prefectural Government, Japan (2018). Fukushima Revitalization Station. Retrieved from: http://www.pref.fukushima.lg.jp/site/portal-english/

Japanese Reconstruction Agency (2018). Retrieved from: http://www.reconstruction.go.jp/english/